Tapatios, the people of Guadalajara, Mexico, are known for their warmth and hospitality. I first encountered their friendliness during a summer semester abroad program in college. Arriving with my guitar and blond and Black roommates made it especially easy to meet people, since our crew stood out.

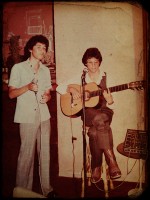

My first week in town my classmates helped celebrate my 21st birthday at La Copa de Leche, a 2nd floor restaurant with balcony seating overlooking the street. After dinner, we went upstairs to Las Calandrias lounge, named for the horse-drawn carriages that tour the city. Musicians Fernando and Chavo were performing popular Mexican and Latin American ballads on guitar and piano. When they took a break, the two young men were drawn like magnets to our obviously foreign group.

Chavo set his guitar down next to me. I started fingering a few chords. Before you know it, I was a regular part of the late night set at Las Calandrias, singing Spanish and American pop and folk songs for drinks.

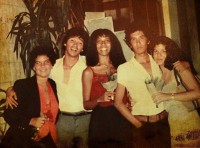

The blond found another handsome distraction, but the dynamic duo of Fernando and Chavo became part of our crowd, taking us swimming at a local pool, or for picnics in the country with appropriate musical accompaniment. They introduced us to many places we probably wouldn’t have discovered on our own. I was sorry to have to leave when the eight weeks was up.

With such special memories, I had some trepidation returning to Guadalajara years later. How could the Guadalajara of today compete with such great memories? I was traveling with a camera instead of a guitar, and I was on my own, sans blond beacon. On my own, I blend in pretty well.

I arrived at the Quinta Real Hotel, a colonial-feel luxury complex near the Minerva Fountain on Calle de las Americas. I knew I was coming in at the end of the Fiestas Octubre arts celebration. I was too late for the grand processions of the morning, but I was hoping to catch some photogenic folklorico dancers or other activities happening that evening.

As a working travel photographer and writer, I don’t worry about traveling incognito. Loaded with my heavy camera gear, I approached the young man at the concierge desk to see if he had a festival schedule.

The concierge was a dapper 20-something young man in suit and tie with slicked back hair. His name tag identified him as Adalberto. Despite his impeccable English, I chose to revive my rusty Spanish in asking for guidance. At my request, he pulled out the day’s newspaper and checked the program for the festival. I was in luck; there were folk dancers and mariachis scheduled to perform downtown in the Plazas that evening.

Just then the sales manager, Arturo, came by to talk to Adalberto. When he heard that I was heading downtown to the Fiestas, he volunteered to give me a ride. He was new to Guadalajara himself and hadn’t seen any of the festivities. Adalberto decided he didn’t have anything better to do either and he was about to get off work, so he came along as well.

I don’t know if it was the big camera having a similar magnetic effect to a guitar, or simply Tapatio hospitality at work, but I set off with my two companions for the Centro.

We found the Mariachi Internacional de Guadalajara playing in the gazebo or kiosko at Plaza de las Armas. They were just getting started as twilight was darkening to night. The lights of the gazebo framed the mariachis with a backdrop of the cathedral lit up against a sky that went deep cobalt for a few moments before settling into black. The sound of trumpets, guitarrons and voices filled the air. A perfect Guadalajara moment.

It lingered until the last notes of Jalisco no te Rajes extolled the virtues of Guadalajara as “the rarest pearl” of the state of Jalisco, whipping the crowd into a rousing final chorus an hour later.

Colonial Guadalajara is laid out with four plazas forming a cross around the Cathedral along Avenida Hidalgo and Avenida Alcalde. The Plaza Guadalajara is in front of the church to the west, the Rotonda on the north side to the left and Plaza de Armas to the right. Behind the cathedral, the two-block Plaza Liberacion makes up the long branch of the cross with Teatro Degollado at its base. Beyond the theatre to the east, Paseo Degallado is a 3-block pedestrian shopping zone built up over the last couple decades, adding kitschy tourist attractions like Ripley’s Believe it or Not to the traditional colonial offerings before ending at Plaza Tapatia.

After listening to the mariachi concert, we decided to walk around the Cathedral to Plaza Liberacion, where we found stone carvers competing in the National Stonework Competition. Some of them had taken off for the night, but others were still hard at work chiseling massive rocks into abstract shapes, bears, lions, Madonnas and other religious figures.

We continued past the Teatro Degollado with its European-style allegory above the front colonnade, and in the next block found a temporary outdoor stage had been set up at the beginning of the Paseo Degollado. For the next hour we enjoyed a spectacle of folklorico dancers. Raven-haired beauties in jewel-toned blouses swirled their flowered skirts; charros in cowboy hats kicked up their boots; masked viejitos in serapes shuffled in circles; and nimble dancers wielded machetes for our nail-biting entertainment.

My two escorts were reveling in their spontaneous immersion into their own culture, away from the day to day of hotel business. The music followed us back to the Quinta Real, where, in no hurry to end the evening, we went to the restaurant and enjoyed a late dinner with a background of original compositions by local pianist José Luis Altamirano.

Over dinner, I shared tales of my time as a lounge singer at Las Calandrias, only to be told that the restaurant and bar were long gone, replaced by a new university building. That chapter in my history firmly closed, to be revisited no more.

In the morning, Arturo introduced me to his boss, Carlos, the hotel’s general manager. “Carlos loves to sing,” Arturo told me. “I told him you know how to sing Spanish songs.”

“You should come with us tonight,” Carlos invited, “Some of the managers are having an informal meeting at a great Cuban Bar.”

So after a day of exploring Guadalajara on my own, I joined the Quinta Real crew at La Bodeguita del Media, a two-level Cuban restaurant and nightclub advertising 2 for 1 mojitos on a yellow banner out front. In addition to the lethal rum beverages, the draw of the Bodeguita was the music.

Two different roaming bands of musicians moved from table to table taking requests, one upstairs, one downstairs. Then they’d switch. When the musicians came our way, Carlos was ready with his first request – a song I didn’t recognize – which he sang along with gusto. Since the band played predominantly Cuban music, I didn’t recognize much besides the rhythm.

Others at our table joined in for a few songs, but I could only sing along on a few choruses, so Carlos insisted that I make a list of songs that I know in Spanish to see if the musicians knew any of them. Since I know mostly Mexican mariachi, folk songs and ballads, they didn’t, but Carlos did, so we traded a few choruses across the table after the musicians had moved on. This was how I remembered Guadalajara – warm welcoming people making music together. I felt right at home.

The next night I found out that Carlos had an ulterior motive when asking for the list of songs I knew. After most of the patrons had cleared out of the hotel restaurant and bar, Carlos approached me. Nodding toward the smiling guitarist who had been entertaining us for the last couple hours, he said, “He knows how to play Como and El Quelite,” – two songs from my list. As it turned out he also knew some Beatles, John Denver, Simon and Garfunkel and a lot of other songs Carlos and I could join in, so we kept our little jam session going into the wee hours of the morning.

As I headed reluctantly to the airport the next day, already feeling nostalgic and grateful for the wonderful memories that I would have from this trip, the last verse of El Quelite kept running through my head, defining my relationship with this beautiful city and its people.

Yo no canto porque se, ni porque mi voz sea buena. Canto porque tengo gusto en mi tierra y en la ajena.

Mañana, me voy mañana. Mañana me voy de aquí. El Consuelo que me queda, que se han de acordar de mi.

I don’t sing because I know how, nor because my voice may be good. I sing because I enjoy my country and others too.

Tomorrow, I go tomorrow. Tomorrow I go from here. My only consolation is that they’ll remember me.

After all, how many gringas show up knowing all the verses to El Quelite?

Read more about Things to Do on a Rainy Day in Guadalajara.

Guadalajara, Jalisco is known as the most Mexican of Mexican cities. It is the birthplace of such Mexican icons as Mariachi, Tequila and the Charro or Mexican cowboy. Many of the traditional folk arts we recognize as Mexican are also created here. It is Mexico’s second largest city with a population of 1.6 million in the City proper and over four million in the metropolitan area. Greater Guadalajara includes the municipalities of Tlaqupaque, Zapopan and Tonolá as well as the city of Guadalajara. Each has its own distinct historical center, but their modern suburbs have become intertwined.

Guadalajara, Jalisco is known as the most Mexican of Mexican cities. It is the birthplace of such Mexican icons as Mariachi, Tequila and the Charro or Mexican cowboy. Many of the traditional folk arts we recognize as Mexican are also created here. It is Mexico’s second largest city with a population of 1.6 million in the City proper and over four million in the metropolitan area. Greater Guadalajara includes the municipalities of Tlaqupaque, Zapopan and Tonolá as well as the city of Guadalajara. Each has its own distinct historical center, but their modern suburbs have become intertwined. The “pearl of Jalisco,” as the city is known, has a wonderful climate for year-round outdoor activities with average high temperatures in the 70s and 80s all year long. June through September is the rainy season, with July averaging 20 days of rain. El Nińo conditions extended the rain through October this year. That doesn’t mean that it will rain all day long for days at a time, but you should always be prepared for a cloudburst.

The “pearl of Jalisco,” as the city is known, has a wonderful climate for year-round outdoor activities with average high temperatures in the 70s and 80s all year long. June through September is the rainy season, with July averaging 20 days of rain. El Nińo conditions extended the rain through October this year. That doesn’t mean that it will rain all day long for days at a time, but you should always be prepared for a cloudburst. patio restaurant for the duration of the downpour. I could have ensconced myself with a good guide book in my golden suite to wait out the rain at this all-suite boutique hotel with a colonial flavor. I could have taken up residence in the bar for a signature Mariana (a kiwi strawberry margarita with salt and chili powder on the rim of the glass), or lingered in the restaurant to enjoy any of Chef Gabriel Duram’s scrumptious meals accompanied by a variety of musicians who play for breakfast, lunch and dinner. I could have explored the collection of one-of-a-kind historical Spanish and Mexican artwork displayed throughout the hotel’s public areas, or spent some time catching up on email in the business center. And to tell the truth, I did all of those things, but still found some rainy and not-so rainy moments to explore other rainy day possibilities in this beautiful city.

patio restaurant for the duration of the downpour. I could have ensconced myself with a good guide book in my golden suite to wait out the rain at this all-suite boutique hotel with a colonial flavor. I could have taken up residence in the bar for a signature Mariana (a kiwi strawberry margarita with salt and chili powder on the rim of the glass), or lingered in the restaurant to enjoy any of Chef Gabriel Duram’s scrumptious meals accompanied by a variety of musicians who play for breakfast, lunch and dinner. I could have explored the collection of one-of-a-kind historical Spanish and Mexican artwork displayed throughout the hotel’s public areas, or spent some time catching up on email in the business center. And to tell the truth, I did all of those things, but still found some rainy and not-so rainy moments to explore other rainy day possibilities in this beautiful city. names. The official name is Mercado Libertad or Liberty Market. Most locals refer to it as Mercado San Juan de Dios ( St. John of God Market) after the nearby church and neighborhood of the same name. Still others call it Mercado “Taiwan de Dios” for the piles of imported electronics sold there. By any name, Latin America’s largest indoor market can keep you occupied and out of the rain for a good long while, even if you’re not a shopper. If you are a shopper, feel free to haggle, but keep in mind that wages in Mexico are really low, so don’t try to drive too hard a bargain.

names. The official name is Mercado Libertad or Liberty Market. Most locals refer to it as Mercado San Juan de Dios ( St. John of God Market) after the nearby church and neighborhood of the same name. Still others call it Mercado “Taiwan de Dios” for the piles of imported electronics sold there. By any name, Latin America’s largest indoor market can keep you occupied and out of the rain for a good long while, even if you’re not a shopper. If you are a shopper, feel free to haggle, but keep in mind that wages in Mexico are really low, so don’t try to drive too hard a bargain. With over 1000 vendors, there’s not much for sale that can’t be found at the Mercado. The problem is that the market is so vast and the aisles are so narrow, that many people wander around for an hour and think they’ve seen it all, when they’ve barely scratched the surface. I can’t claim to be an expert. I spent about three hours and still only saw a fraction of what there was to see.

With over 1000 vendors, there’s not much for sale that can’t be found at the Mercado. The problem is that the market is so vast and the aisles are so narrow, that many people wander around for an hour and think they’ve seen it all, when they’ve barely scratched the surface. I can’t claim to be an expert. I spent about three hours and still only saw a fraction of what there was to see. the plazas downtown, you’ll most likely be approaching from the north or west. From the north, you’ll probably want to skip most of the housewares in the outer booths along the long north side. If you don’t have a lot of time, walk along the outside of the market to where you see the more traditional copper vats and clay cooking pots.

the plazas downtown, you’ll most likely be approaching from the north or west. From the north, you’ll probably want to skip most of the housewares in the outer booths along the long north side. If you don’t have a lot of time, walk along the outside of the market to where you see the more traditional copper vats and clay cooking pots. Keep an eye out on your way for some of the traditional Mexican sweets, like the sugar skulls for Day of the Dead. Then look for the basket vendor at the corner of an aisle that looks through to daylight on the other side. That should take you past hand made wooden toys, maracas and other arts and craft vendors on the way in to the patio.

Keep an eye out on your way for some of the traditional Mexican sweets, like the sugar skulls for Day of the Dead. Then look for the basket vendor at the corner of an aisle that looks through to daylight on the other side. That should take you past hand made wooden toys, maracas and other arts and craft vendors on the way in to the patio. On the closest (north) side of the patio, you’ll find hand-woven baskets and bags, papier-mâché masks and dolls, clay and pottery miniatures and a wide variety of folk arts from the Guadalajara Metro area, the most important producer of hand crafts in the country.

On the closest (north) side of the patio, you’ll find hand-woven baskets and bags, papier-mâché masks and dolls, clay and pottery miniatures and a wide variety of folk arts from the Guadalajara Metro area, the most important producer of hand crafts in the country. But if you’re looking for Mexican-made leather boots and sandals, you might want to start at the northern entrance that leads straight up the stairs to a row of cobblers and shoe vendors. You may spot one of Maximo Pelayo’s giant huarache sandals hanging at the top of the stairway above the rows of footwear made for normal-sized folks. His giant huaraches have found their way into Mexican restaurants and other establishments on both sides of the border. He makes them right there on the spot.

But if you’re looking for Mexican-made leather boots and sandals, you might want to start at the northern entrance that leads straight up the stairs to a row of cobblers and shoe vendors. You may spot one of Maximo Pelayo’s giant huarache sandals hanging at the top of the stairway above the rows of footwear made for normal-sized folks. His giant huaraches have found their way into Mexican restaurants and other establishments on both sides of the border. He makes them right there on the spot. Vendors tend to be grouped together by product categories, so if you’re looking for something in particular, it’s best to ask directions to that part of the market, although within this order there is also a random mix of vendors outside of their product zone. Most vendors know numbers and prices in English. Some also know enough to point you in the right direction to find what you’re looking for. Toiletries, perfumes, watches, office supplies, groceries

everything but packaged liquor and pharmaceuticals can be bought at the market.

Vendors tend to be grouped together by product categories, so if you’re looking for something in particular, it’s best to ask directions to that part of the market, although within this order there is also a random mix of vendors outside of their product zone. Most vendors know numbers and prices in English. Some also know enough to point you in the right direction to find what you’re looking for. Toiletries, perfumes, watches, office supplies, groceries

everything but packaged liquor and pharmaceuticals can be bought at the market. There’s a section for handmade leather goods, from belts to jackets to boots to hats. There are long counters of silver and gold jewelry with guitars hanging overhead, an odd, but common combination in this market. Guitars seem to go with anything.

There’s a section for handmade leather goods, from belts to jackets to boots to hats. There are long counters of silver and gold jewelry with guitars hanging overhead, an odd, but common combination in this market. Guitars seem to go with anything. On the north side of level 2, along with cobblers and other shoe vendors, hardware (hammers, saws, etc.) can be found next to music CDs and electronics. Contemporary clothes and lots more shoes are on level three. If you’re looking for Mexican blankets, traditional clothes, sombreros or T-shirts, the first aisle along the east end closest to the parking structure has a good selection.

On the north side of level 2, along with cobblers and other shoe vendors, hardware (hammers, saws, etc.) can be found next to music CDs and electronics. Contemporary clothes and lots more shoes are on level three. If you’re looking for Mexican blankets, traditional clothes, sombreros or T-shirts, the first aisle along the east end closest to the parking structure has a good selection. Levels two and three are open in the middle like a shopping mall, but rather than a fountain in the middle, you look down on the roofs of the first floor stalls. I could look across from the east side of level two and see all the food vendors on the west side, but I never made it over there in my three hours of exploring. I did come across another area of sandwich booths on the south side selling a variety of tortas (sandwiches on large rolls) between the butchers and the spice vendors.

Levels two and three are open in the middle like a shopping mall, but rather than a fountain in the middle, you look down on the roofs of the first floor stalls. I could look across from the east side of level two and see all the food vendors on the west side, but I never made it over there in my three hours of exploring. I did come across another area of sandwich booths on the south side selling a variety of tortas (sandwiches on large rolls) between the butchers and the spice vendors. For American sensibilities, the butcher aisle is a bit of a culture shock. Every part of the animal is hanging in front of you, exposed to the air and available for purchase. Seeing all the hanging heads, feet and intestines didn’t really give me much of an appetite, but I found it fascinating.

For American sensibilities, the butcher aisle is a bit of a culture shock. Every part of the animal is hanging in front of you, exposed to the air and available for purchase. Seeing all the hanging heads, feet and intestines didn’t really give me much of an appetite, but I found it fascinating.